For the last three years of my undergrad, I was an RA (or something related) in one of my school’s residences: it was a fairly easy job, came with decent and cheap accomodations. It was a ton of fun, helping scared young people find their feet, organizing events, being the gentle enforcer.

Every year, for a week before the students came, we did training and preparation. We would get some information about the students that were going to move onto each floor, including hometown and high school. The ones that we took special care to track down were the young women from all-girls high-schools. The mix of freedom, naivety, and gentle rebellion made them, uniquely vulnerable. Mostly nothing happened. I don’t think that any of my students ever got into serious situations, but I clearly remember some very close calls.

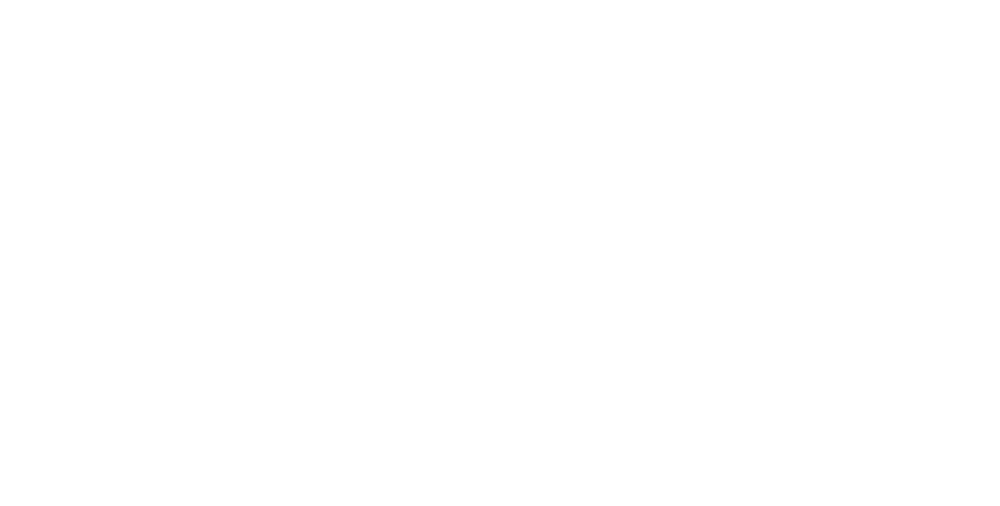

Memories of these moments came through vividly while reading Annie Ernaux‘s memoir A Girl’s Story. Published in 2020, the book recounts the summer of 1958, when an 18-year-old Ernaux left her all-girls Catholic high school and took a job as a counsellor in a co-ed camp. It was her first time in an environment with boys her age (and a little older), and almost immediately, things begin to unravel. Ernaux tells the story with her usual spare and brutally honest style, but in this case she goes a step further. She writes about her younger self with the third person, denying her the comfort of grown-up understanding or easy forgiveness.

The book opens with an account of a clearly non-consensual sexual encounter, though Ernaux avoids framing it in simplified terms. What follows isn’t a narrative of victimhood but a reckoning with memory, language, shame, and silence. Young Annie is alienated from the other counsellors, lost in confusion and self-blame, unable to process what has happened or how it’s changed her. She drifts through the rest of the summer and returns to school, where she continues to excel academically even as she is emotionally undone. She develops an eating disorder that causes further health concerns.

What’s most striking about A Girl’s Story isn’t the trauma itself, but the precision with which Ernaux revisits it. She refuses to impose a clear narrative arc, or any healing or insight. The prose is cold and clinical. She dissects her past with the detachment of a researcher, constantly looping back to try to understand not just what happened, but how it affected her after the fact, and how she came to think about it the way she did.

Ernaux doesn’t look back with nostalgia or judgment. She doesn’t reclaim anything. Instead, she writes toward a difficult recognition: the person she was, and the world she was thrown into, can’t be separated. She doesn’t flinch from what happened, but she also doesn’t turn it into a story of survival or redemption.

Reading A Girl’s Story, I kept thinking about how little has changed. The specifics of time and place and technology are different, but the dynamics remain: the social pressures that leave some people exposed and others untouched, the ease with which harm accepted as part of the story of becoming an adult. A Girl’s Story is another upsetting and difficult memoir, the type of thing Ernaux does better than anyone.